I feel a sense, a responsibility, to carry on the wonderful mission of the unknown bards who created the spiritual, whom we are not privy to know their names.

--Moses Hogan

Have you listened to our Sunday morning choral program Sacred Classics? Maybe you’ve heard a few songs on your way to church or while out running errands. If so, chances are you’ve heard me play spirituals such as “The Battle of Jericho,” “Steal Away,” “Wade in the Water,” and “Great Day” performed by the Moses Hogan Singers. One of my favorite albums of spirituals features Barbara Hendricks with the Moses Hogan Singers. It’s called Give Me Jesus. Most of the songs in the collection were arranged by Moses Hogan. They have an artful sensibility and a vibrancy—at times conveyed in an intense stillness—that ennoble and make palpable the yearning and joy of the songs’ creators. And, the performances are simply stunning.

Unfortunately for me, like Franz Schubert, my days as a chorister ended when my voice broke, but if you sing in a community or church choir, you may have performed arrangements by Moses Hogan. For Black History Month, I’d like to pay tribute to this American master who dedicated his brief life to keeping alive the oral tradition of African American spirituals and honor their anonymous bards.

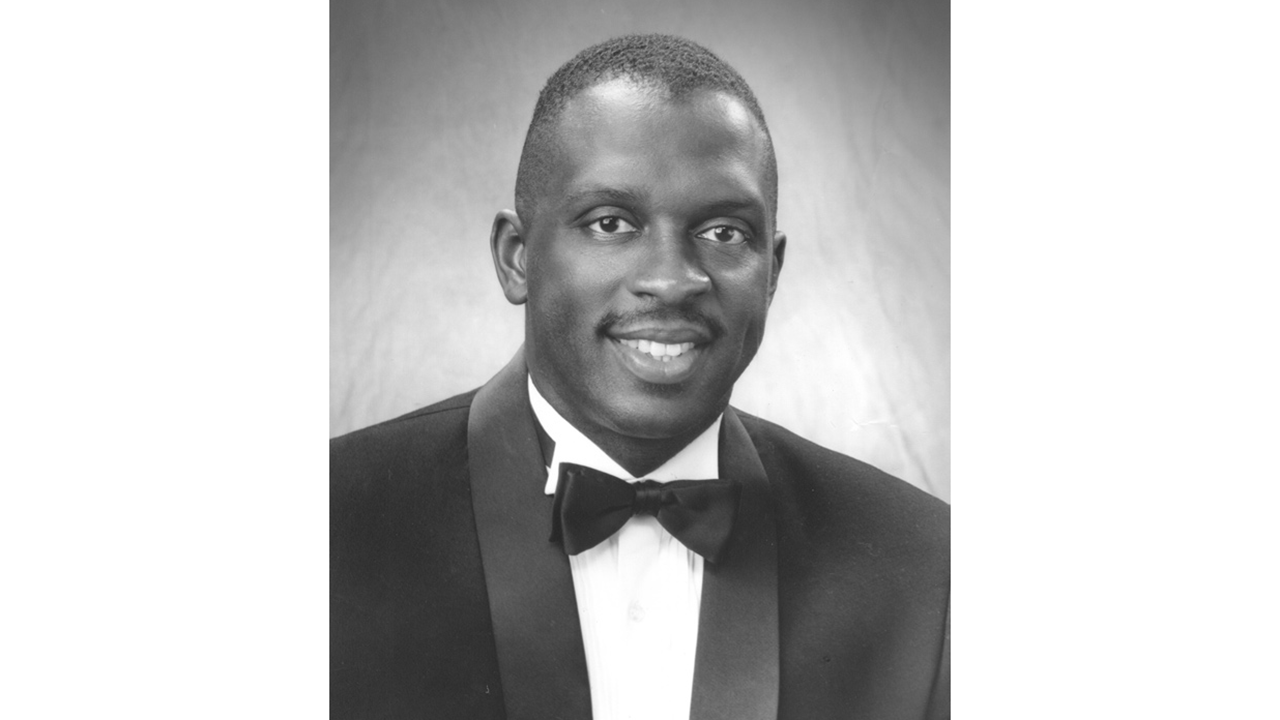

Moses Hogan was recognized as one of the most celebrated directors and arrangers of spirituals when he died of a brain tumor in 2003 at age 45. In his short lifetime, he published more than 80 original arrangements of African American spirituals and formed several choirs for their performance.

The term “spiritual” comes to us from the King James Bible translation of St. Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians: “Speaking to yourselves in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody in your heart to the Lord.” Some of the improvised religious songs we know as spirituals were created in the “praise houses” of African slaves. The gatherings included call-and-response singing and dancing. Many songs reflected an identification with the suffering of Jesus, hope for salvation, and a connection to Moses who led his people to freedom. Some songs encoded messages about secret meetings or directions for escape. Others originated in the camp meetings of the evangelical revival movement known as the Second Great Awakening. One white minister, who overheard these songs, recorded these impressions:

In the blacks’ quarter, the coloured people get together, and sing for hours together, short scraps of disjointed affirmations, pledges, or prayers, lengthened out with long repetition choruses. These are all sung in the merry chorus-manner of southern harvest field, or husking-frolic method, of the slave blacks. . . . I have known in some camp meetings, from 50 to 60 people crowd into one tent, after the public devotions had closed, and there continue the whole night, singing tune after tune, (though with occasional episodes of prayer) scarce one of which were in our hymn books.[ii]

From the energetic, emotional, and noisy atmosphere of these revival meetings, a new style of religious song emerged.

Moses Hogan hailed from the South. He was born in New Orleans, six months before the Civil Rights Act of 1957 was signed into law. He began his musical life as a pianist and accompanist for his church and continued his formal musical studies at Oberlin Conservatory of Music, the Juilliard School of Music, and Louisiana State University. In 1980, he founded the Moses Hogan Chorale which was devoted to the promotion of African American spirituals. In 1998, he formed the Moses Hogan Singers which debuted that year at Alice Tully Hall in the World Projects Corporation New York Choral Festival. The Moses Hogan Singers also made their recording debut in 1998 with soprano Barbara Hendricks on that release entitled Give Me Jesus.

Let me share with you what one reviewer at the time wrote about this album: “Give Me Jesus, if this is possible, is the sort of CD that makes you a little better every time that you hear it.”[iii] I believe songs have that power, and you don’t have to be a singer or a church-goer to feel inspired by these works.

By my count, the Moses Hogan Singers released four more recordings following their debut album, and I’m fairly certain they’re all still available. During Black History Month and throughout the year, you’ll continue to hear me share with you the work of Moses Hogan as arranger and choral director, honoring the anonymous bards who created the African American spirituals. I invite you to listen in, Sundays from 7:00 to 9:00 a.m. on WNED Classical.

Scott Sackett

[i] Hogan, Moses. Sixth World Symposium on Choral Music: Composers’ Forums, Minneapolis, August 3-10, 2002, 2003, 2104310a1da50059d9c5-d1823d6f516b5299e7df5375e9cf45d2.ssl.cf2.rackcdn.com/nmbx/assets/49/symposium.pdf.

[ii] Watson, John F. Methodist Error; Or, Friendly, Christian Advice, to Those Methodists, Who Indulge in Extravagant Emotions and Bodily Exercises. D. & E. Fenton, 1819.

[iii] Tuttle, Ray. “Classical Net Review - Give Me Jesus - Barbara Hendricks.” Classical Net, 1999, www.classical.net/music/recs/reviews/e/emi56788a.php.