No. 5

Barber: Adagio

Barber’s Adagio for Strings

In 2004 the BBC’s “Today” show launched a survey to discover the “saddest” piece of classical music ever written. Among the top 5 were “Dido’s Lament” from Purcell’s opera “Dido and Aeneas”, Richard Strauss’ late work for 23 solo strings “Metamorphosen”, the “Adagietto” movement for Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 and even Billy Holiday’s rendition of Hungarian composer Rezső Seress song “Gloomy Sunday”. But saddest piece of all by a wide margin was the “Adagio for Strings” by Samuel Barber. Its association with public memorial occasions of all kinds started with the death of Franklin Roosevelt, when after the announcement of the President’s death it was played on the radio. The public events: the lying in state, the procession from the Capital Building to Union Station, the arrival at Hyde Park and the funeral itself were all carried live on the radio and Barber’s Adagio was played at every break in the ceremonies that stretched over 3 days.

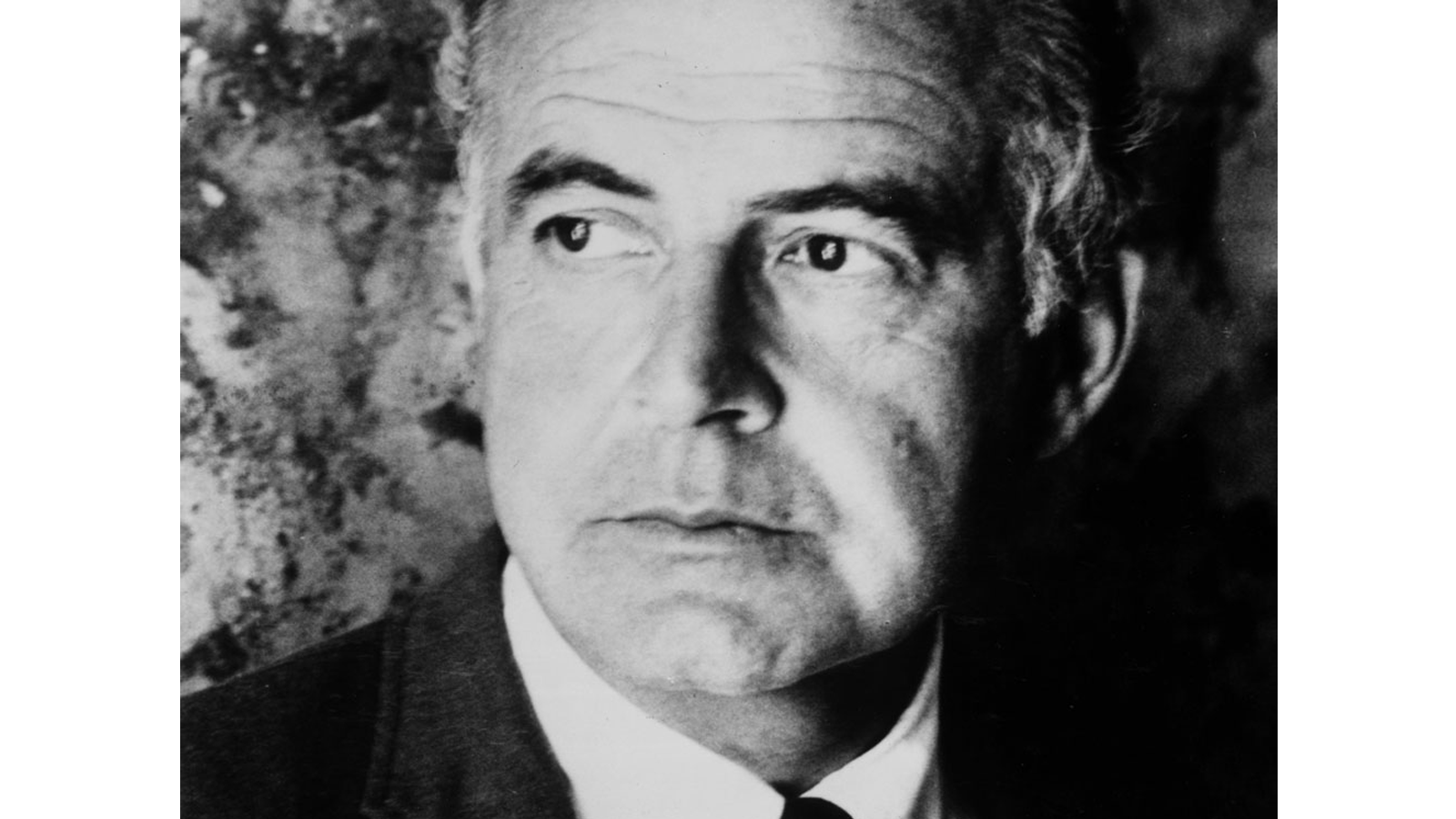

In the summer of 1936, Samuel Barber was in Italy with his lover Gian Carlo Menotti, an Italian who was a classmate at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. Both young men were studying to become composers. That summer Barber composed a string quartet inspired he claimed by the “Georgics” by Virgil. Sometime in that summer Menotti and Barber are invited to Arturo Toscanini’s retreat in the Italian Alps. There Barber shows Toscanini the manuscript of his new quartet. Toscanini tells Barber that fine as the string quartet is the second movement, the adagio would make a great work for strings alone. It is short enough, and beautiful enough, Toscanini told the young man, to find its way into the repertoire of most orchestras. It could become the piece that would launch Barber’s career as a major composer. A year later, Barber did orchestrate the Adagio movement and sent a copy of the orchestration to Toscanini. In the meantime Toscanini had left the New York Philharmonic and agreed to lead a new symphony, the NBC Symphony, primarily a broadcasting and recording orchestra. Barber was surprised to get the orchestration back from Toscanini without comment of any kind. Then in September of 1938 he got a call from Toscanini telling him that Toscanini had programmed Barber’s Adagio for a broadcast with the NBC Symphony in November. That broadcast performance was named in 2005 by the Library of Congress as an “American Treasure”. The rest, as they say, is history, a history that Barber was not always happy about. When told by a friend how wonderful it was that the “Adagio” had become so popular, Barber replied, “I did write other things, you know.” Indeed he did, but what he contributed to the ongoing collection of things humanity has decided to take with it into the future is the world’s “saddest” piece, “The Adagio for Strings”

Top 40 Countdown

A few years ago the listeners to WNED Classical told us what they thought a TOP 40 list of Classical pieces should be. Six hundred and twenty-two different pieces were put forward, and over nine hundred listeners participated. The result, The WNED Classical Top 40, was both startling and comforting. There were a number of surprises, Stravinsky and Copland made the list; Mendelssohn and Schumann did not! It was comforting to know that the two most popular composers were Beethoven and J.S. Bach. The biggest surprise of all was the piece that crowned the list as No. 1.