How Kleinhans Came To Be | Essay by: Lauren Becker, Kleinhans Music Hall Archivist

We don’t know exactly when it happened. Perhaps it was during an excursion to the opera in Louisville, KY or maybe she simply strolled into his store one day. But sometime in the 1890s, Edward Kleinhans met a blue-eyed, dark-haired musician named Mary Seaton – and the story of Kleinhans Music Hall began.

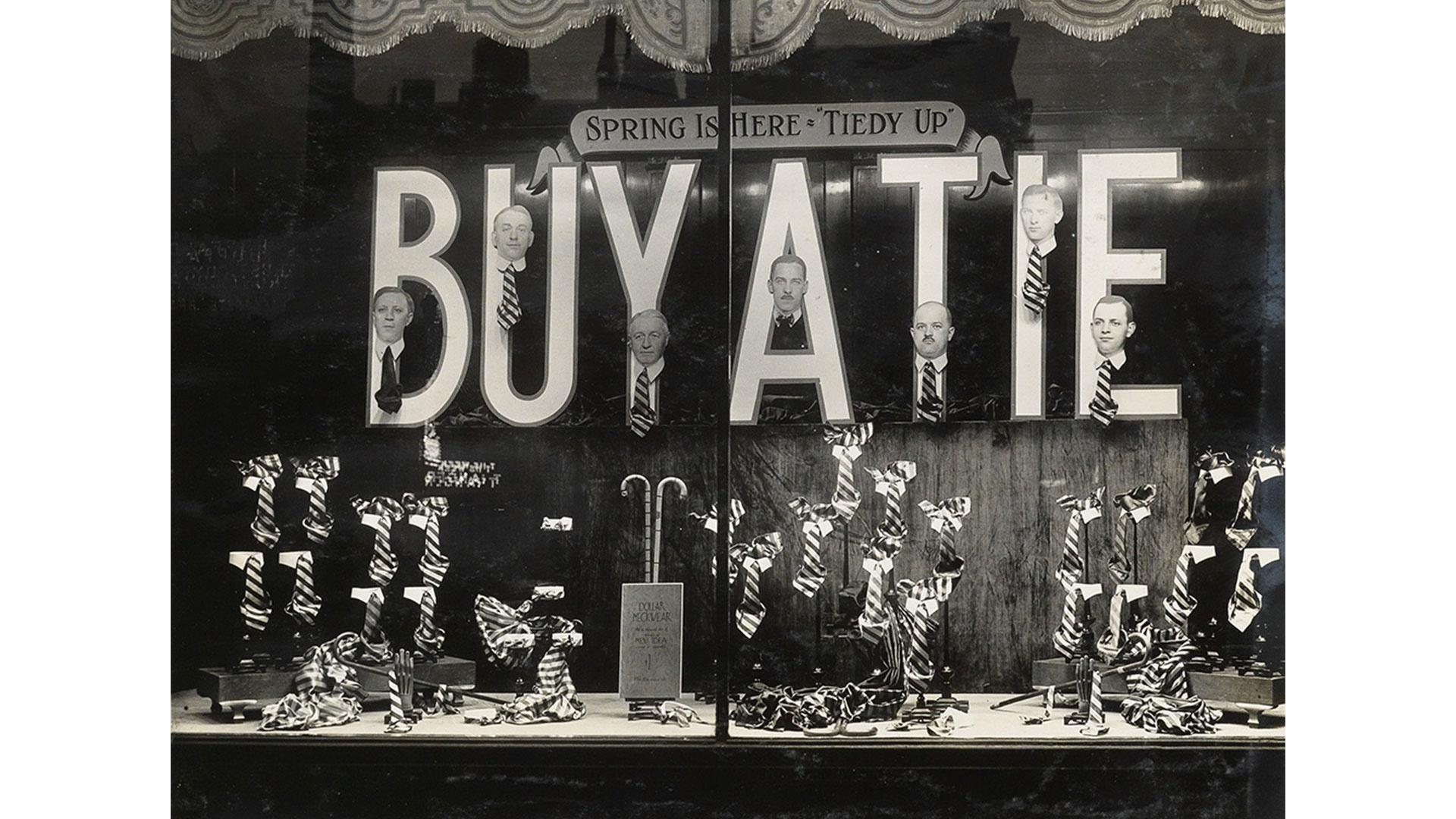

Ed was a creative, up-and-coming businessman specializing in men’s clothing. Mary was a singer and pianist on her way to a career in music. The two fell in love, married, and moved to Buffalo in the electrifying Pan-American year of 1901.

The lifelong romance between Ed and Mary was well known among their many friends. Ed wasn’t a musician, but he delighted in Mary’s music and would sit for hours listening to her play the piano and sing. Their shared love of music took them to concerts of every kind, and as the Kleinhans store grew more successful, they traveled abroad together, seeking out great music halls and performances all over the world.

Back home in Buffalo, however, large concerts meant enduring cold drafts and folding chairs in the Elmwood Music Hall, a hollowed-out, repurposed army drill shed. Ever fond of Buffalo, the Kleinhans dreamed of giving the city something better, something they loved above all else: the joy of experiencing music together in a world-class hall.

When Edward died unexpectedly in February 1934 – and Mary joined him less than three months later – everyone learned just how devoted they were. In honor of Mary, Ed gave the vast majority of the Kleinhans’ estates, nearly $1,000,000, to build a world-class music hall, a hall specifically “for the use, enjoyment, and benefit of the people of the City of Buffalo.”

Because music meant so much in their lives, Edward and Mary Seaton Kleinhans gave Buffalo one of the greatest gifts in its history. Still, their wills didn’t provide specifics about the actual hall itself or how it should be designed and constructed.

How do you turn a million dollars into a music hall?

Inspired by Ed and Mary, another set of devoted people took on the work of turning the Kleinhans’ dream into reality: the Buffalo Foundation, the stewards of the Kleinhans’ estates, known today as the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo.

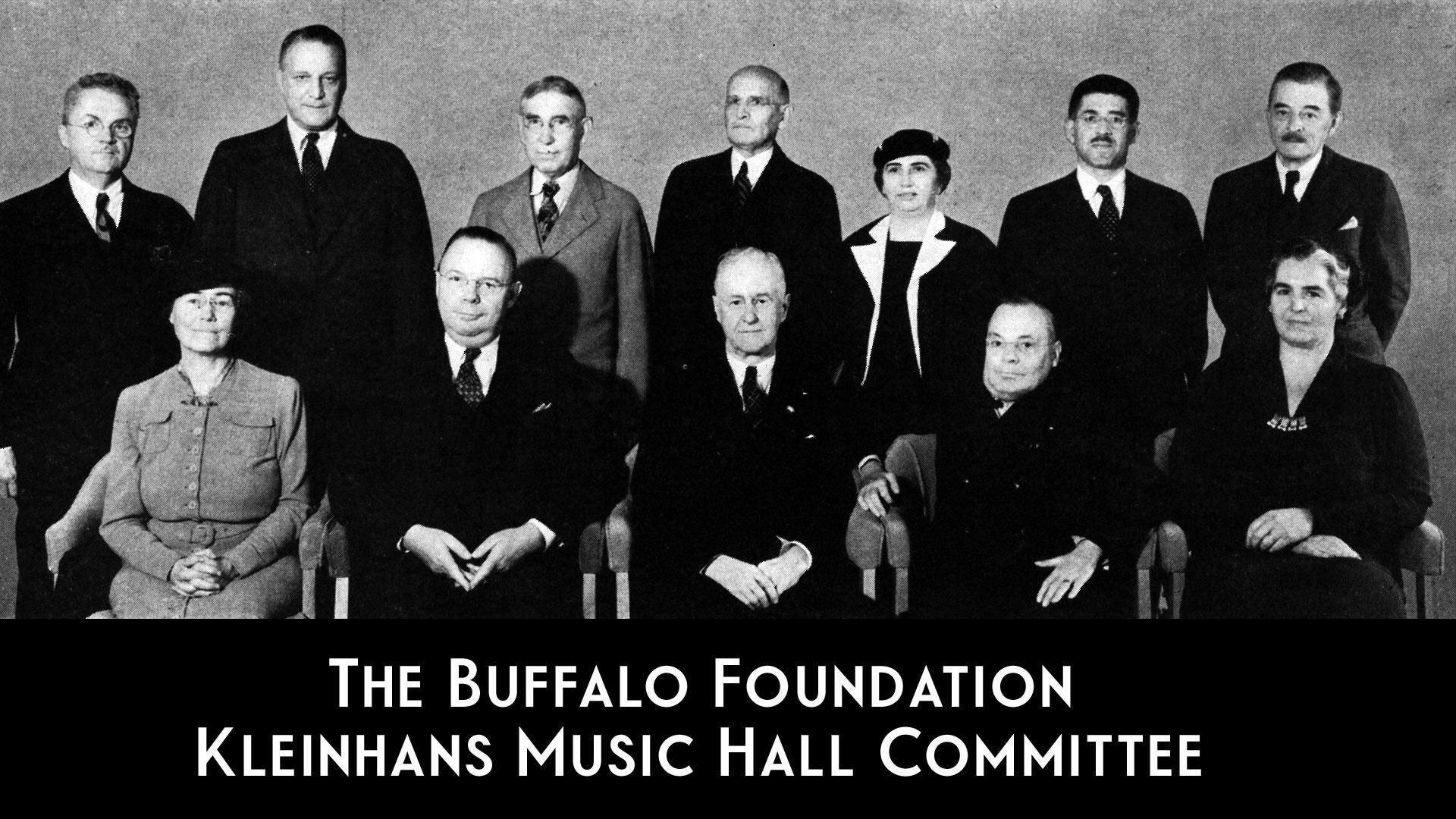

Challenges to the Kleinhans’ dream began almost immediately. When city leaders pushed to have the new hall double as a convention center, the Community Foundation had to set up a special Kleinhans Music Hall Committee to defend the spirit of music at the heart of the Kleinhans’ gift.

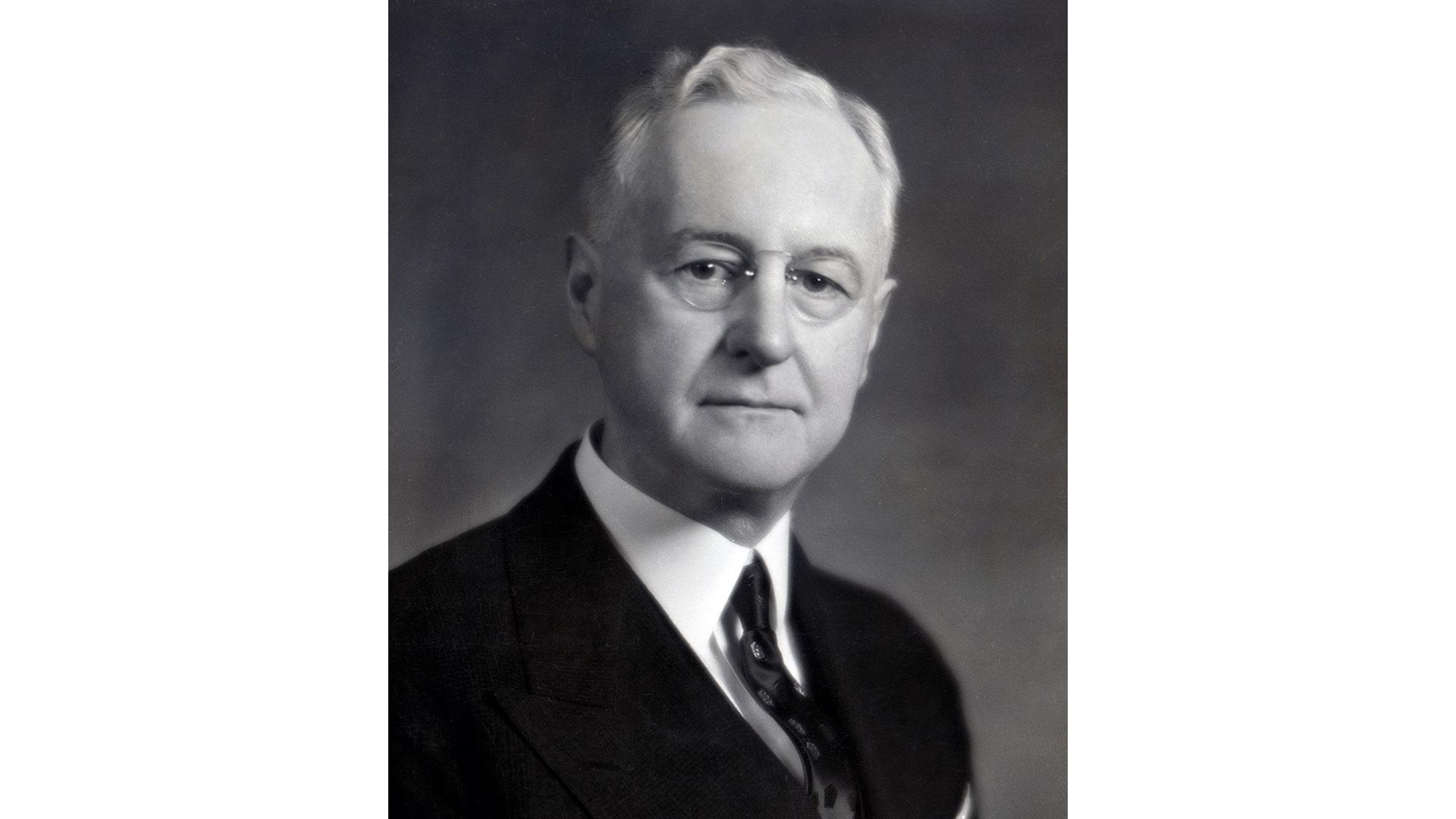

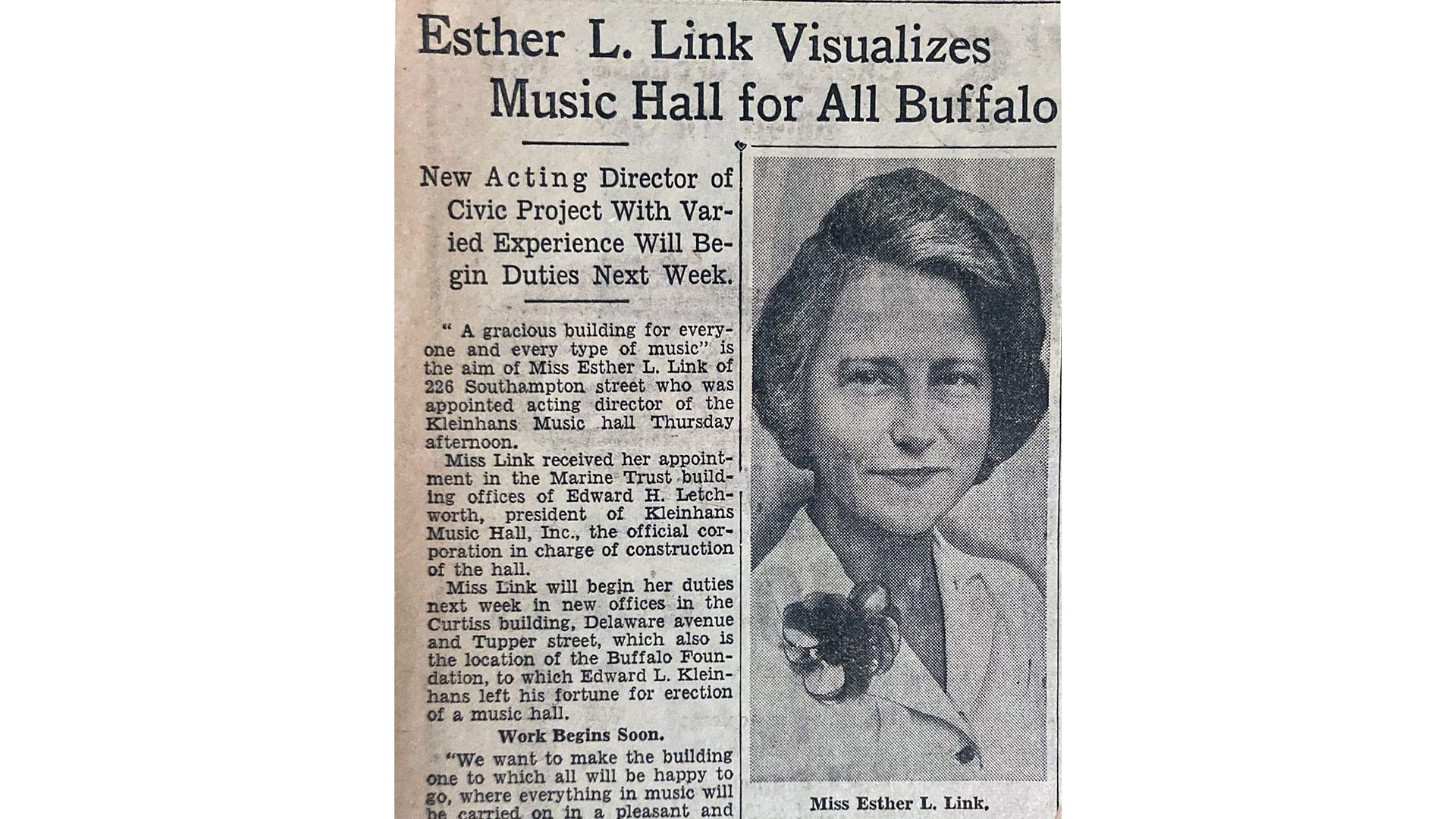

Edward Letchworth led the charge. He, Sara Kerr, Esther Link, and other Music Hall Committee members spent years in service to Kleinhans and the people of Buffalo. They consulted experts, fended off critics, and made thousands of decisions in the process of building our architectural and acoustic masterpiece.

Three decisions were especially consequential for the music hall we know and love today:

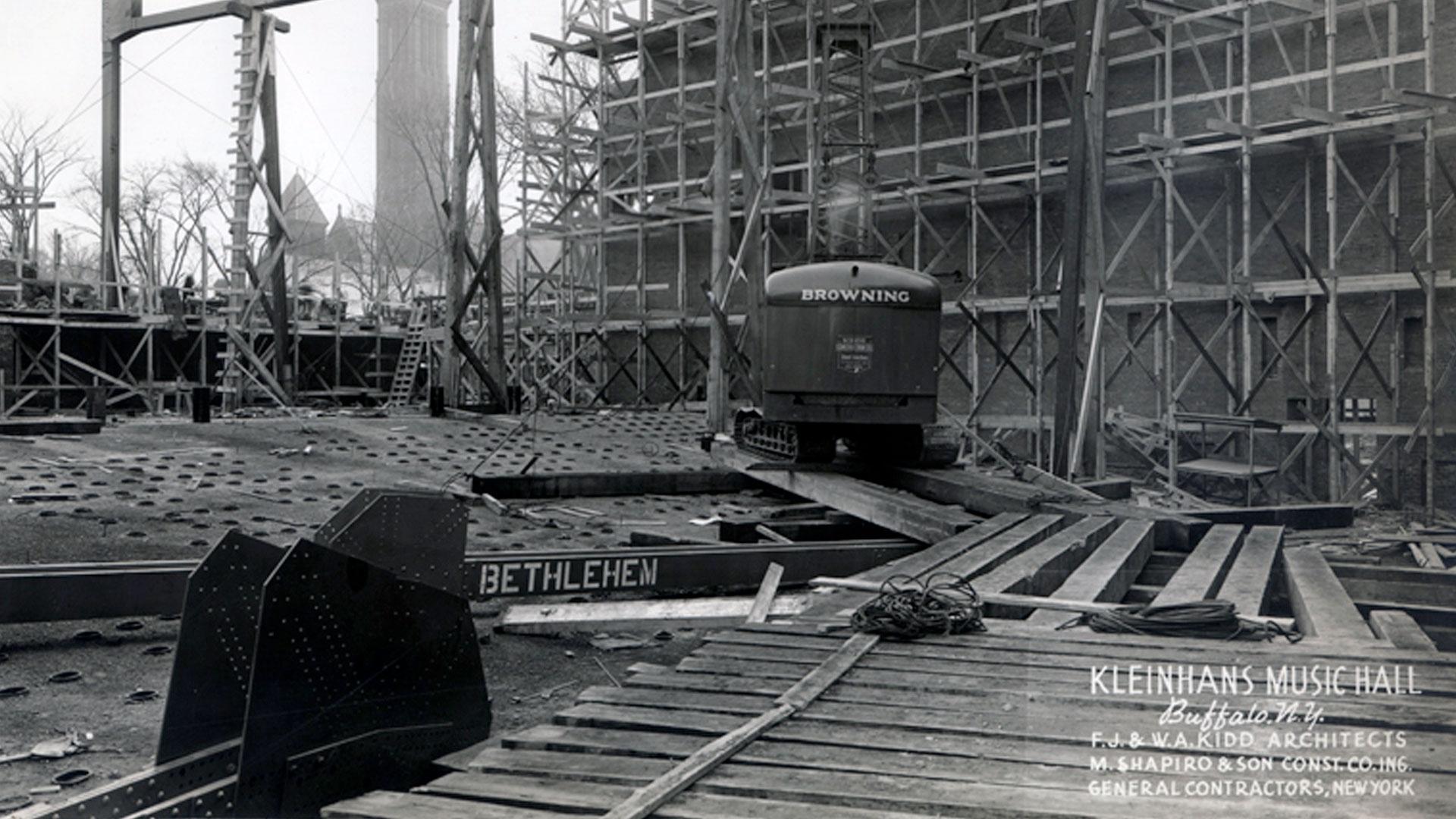

First, the Music Hall Committee decided to seek a grant from the Public Works Administration (PWA) to supplement the funds from the Kleinhans’ estates. The PWA was one of President Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” agencies designed to provide jobs and build civic infrastructure during the Great Depression. It had already been active in other Buffalo projects.

If the Kleinhans grant was approved, the PWA would add a game-changing $500,000 to the hall’s budget, but it would also cause significant difficulties. The PWA only worked with government entities, so they required the Foundation to form a new nonprofit corporation, Kleinhans Music Hall, Inc., governed by a board of directors, the majority of whom had to be City officials. This effectively shifted final decisions about the hall from the Community Foundation, the Kleinhans’ stewards, to the mayor and his appointees, people who knew very little about music or architecture.

After great effort and difficult compromises, the PWA grant came through, but it placed an enormous burden on Letchworth, Kerr, and the other Kleinhans guardians, who would now have to fight for everything they knew was best for the hall.

The second consequential decision came when the Music Hall Committee decided to pursue a modern design for the new hall.

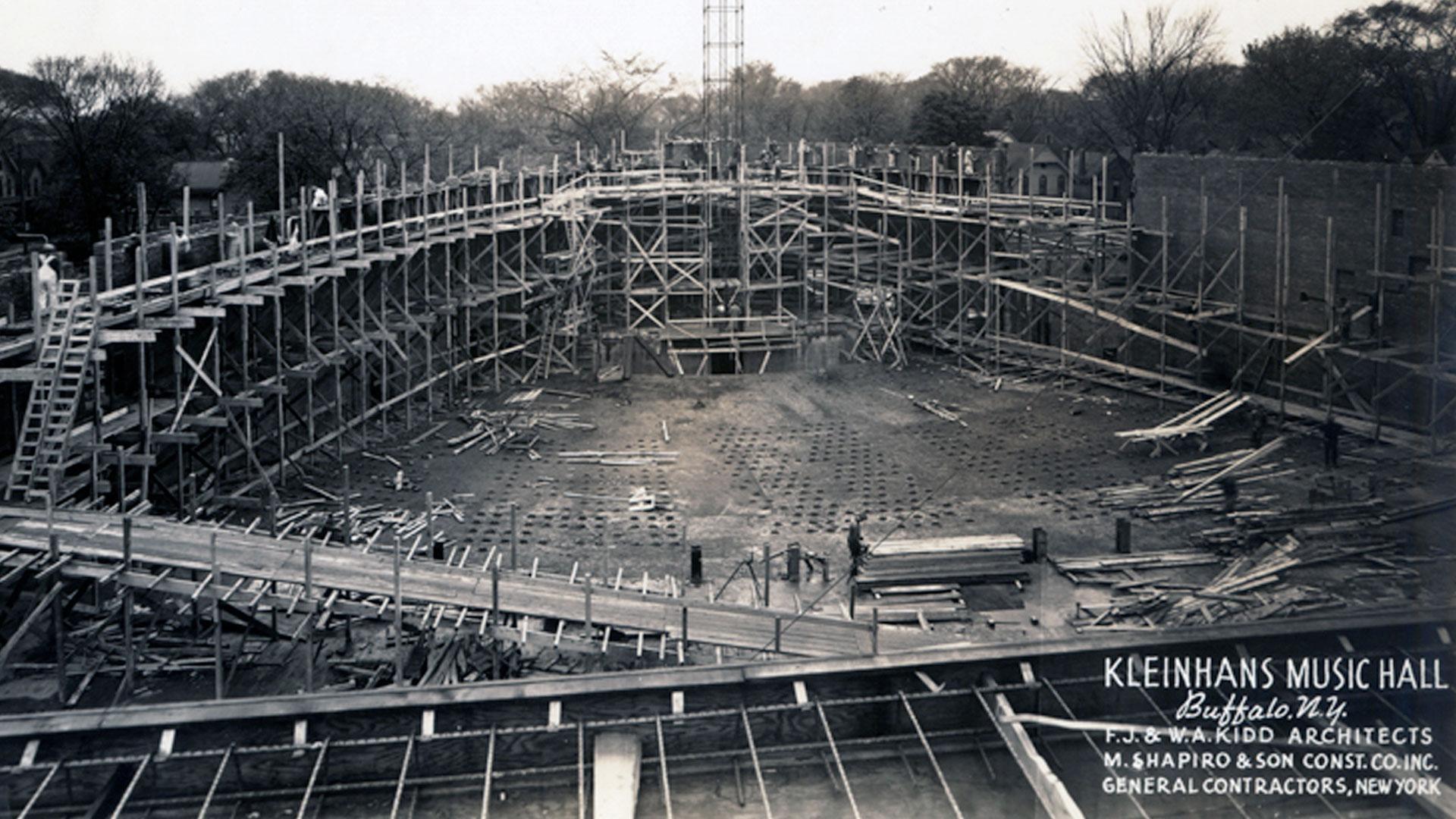

Though some people suggested holding a design competition for Kleinhans Music Hall, the Community Foundation decided early on to hire two well-known local architects for the job: the brothers Franklyn and William Kidd, most famous for designing the Rand Building in downtown Buffalo. With the Kidds on board, Letchworth formed an advisory group to help him work through the thorny question of what architectural style to choose. He and the other members (Franklyn Kidd, Sara Kerr, and Esther Link) agreed a modern design was a good idea, but the Kidds specialized in more traditional styles. They would need a consulting architect, but who?

To his eternal credit, Franklyn Kidd suggested Eliel Saarinen, the pioneering architect from Finland who, incredibly, was living only a short train ride from Buffalo, outside of Detroit, MI, where he was busy designing the new Cranbrook Academy of Arts.

Letchworth and Kidd visited Cranbrook in September 1938 and returned full of enthusiasm but also disappointed. Saarinen declined the role of consulting architect but agreed to hire on as the design architect. However, no one thought they could afford two design architects, and by Saturday night, October 8, Letchworth was ready to send Saarinen the bad news.

Nevertheless, Esther Link was not ready to give up. She worked all night, drafting a letter to Letchworth and the other directors. It argued that Saarinen should be hired as a design architect with the Kidds. A Saarinen design would bring Buffalo a beautiful monument worthy of national renown. Moreover, they shouldn’t worry about money because her family would donate $10,000 to pay for Eliel’s work.

Esther changed everything with her letter. The directors decided to offer $5,000 to Saarinen to draft a plan (Esther’s family did not have to pay). By early December 1938, everyone was comparing two very different models for the new hall: a traditional one from the Kidds and a contemporary one from Eliel Saarinen and his son, Eero.

The most unlikely person made the third and most consequential decision.

With both models in hand, Letchworth called a meeting of the Kleinhans Music Hall, Inc. Board of Directors to vote on which design to use for the new hall – the same Board the PWA had required to be a majority of City officials. He anticipated little difficulty and expected them to vote for the Saarinen design, but, just in case, he compiled a list of eminent architects to advise (and persuade) the city officials if the vote went sideways.

The vote went sideways. Several city representatives could see nothing good in the Saarinen design, and one even compared it to an icehouse! Letchworth called the experts on his list, and the following morning three distinguished architects arrived from New York City. They went to work examining the models and discussing the plans with each other and the directors. By the end of the day, the experts unanimously recommended the Saarinen design. Surely, that would be enough.

When the Board met again for another vote, however, only eight people were present: four representing the Community Foundation, who were all in favor of the Saarinen design, and four representing the city, who were three strong “no’s” plus a fourth who said nothing. Letchworth and the other “pro-Saarinens” worked to bring the city officials to their side but finally had to force a vote. Incredibly, at the last moment, the City Comptroller, William Eckert, decided to abstain, and the Saarinen design won by one vote, 4 to 3.

The Kleinhans’ dream prevailed. Finally, Buffalo would have one of the finest music halls in the world.

Kleinhans Music Hall opened less than two years later, on Saturday, October 12, 1940. Ed and Mary never got to see it themselves, but the hall will forever be an expression of their love for each other, their love of music, and their love for the city where their romantic duet played out. The Kleinhans’ gift ensured that millions of future Buffalonians would have what Ed and Mary loved most: the joy of experiencing music together in a world-class hall.

Kleinhans Music Hall has been owned since 1940 by The City of Buffalo, with Bryon W. Brown as its current mayor. The daily operations of the hall are under the care of Kleinhans Music Hall Management, Inc., a non-profit 501C 3 corporation.

Major funding for Kleinhans’ Gift to Buffalo is provided by Clement & Karen Arrison, The Baird Foundation, Francis & Cindy Letro and Bob Skerker, with additional funding from Bond Schoeneck & King, Peter & Maria Eliopoulos, Daniel & Barbara Hart and Jeremy & Sally Oczek.