Abolition of Slavery in Canada

Freedom Marker: Integrity and Spirituality

by Dr. Bryan Walls

The motto of the Order of Canada is “Desiderates Meliorem Patriam,” Latin for “They Desire a Better Country.” This motto truly applies to the hundreds of known and unknown heroes and heroines who fought and prayed for the abolition of slavery in both the United States and Canada. These abolitionists were men and women of great integrity and faith who believed that slavery was an outrage to the laws of humanity and God.

British Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe was a passionate leader who was opposed to slavery. Simcoe argued that Christian teaching opposed slavery and the British Constitution did not allow it. As the first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada (later to be called Ontario), he pledged to never support a law that “discriminates by dishonest policy between the Natives of Africa, America or Europe.” To his credit Simcoe was a visionary, new-world political leader who was not afraid to speak out against slavery, even when it was not popular to take this stand.

Nine members of his advisory Legislative Council and part of the ruling class in Upper Canada owned slaves and took slavery for granted. In 1793, Simcoe learned that a young slave named Chloe Cooley had been tied with a rope and transported across the Niagara River. Despite her violent resistance, she was sold to a man in the United States. This dramatic event underscored how slaves in Upper Canada had no protection under the law. Her case was brought before Simcoe and his Executive Council in Navy Hall at Newark (now Niagara on the Lake). The resulting legislation repealed the Imperial Statute of 1790 allowing settlers to bring slaves into Upper Canada. This meant that any enslaved seeking the “Canaan Land” of Canada would be automatically free. Any child born to a slave mother after that legislation would become free at the age of 25.

John Graves Simcoe, Chief Justice William Osgoode, Receiver General Peter Russell and others were disappointed by this new anti-slavery law because it was a compromised legislation and did not go far enough toward ending slavery in Canada. Simcoe returned to England in 1798, but his law helped to change public opinion toward slavery in Upper Canada. Thus, thousands of enslaved in the United States, like my great-great-grandfather John Freeman Walls, learned that if they were fortunate enough to cross the 49th parallel of latitude they would automatically be free.

In 1803, Chief Justice William Osgoode placed on the law books the ruling that slavery was inconsistent with British law. Although this did not legally abolish slavery, 300 slaves were set free in Lower Canada (the future Quebec). Citizens who wanted to bargain in the slave trade had no protection from the courts. The decline of slavery took place in Upper Canada as well. The short growing season and cost of feeding and clothing slaves, along with abolitionist sentiment stirred by Simcoe, caused more and more slaves to be set free. Future lieutenant governors of Upper Canada, like Sir Peregrine Maitland, continued the humanitarian spirit of Simcoe and offered Black veterans grants of land. The desire to stamp out slavery in Upper and Lower Canada was so strong that an application from Washington, D.C. to allow American slave owners to follow fugitive slaves into British Territory was flatly denied. Judges who favored abolition were handing down more and more decisions against slave owners; as a result, when the British Imperial Act of 1833 abolished slavery throughout the British Empire, very few slaves remained in Upper and Lower Canada.

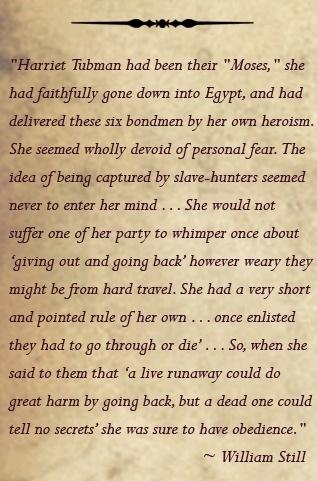

The decades after 1833 saw an increase in abolitionist sympathizers as the fugitive enslaved increased in number and found freedom in Canada. Anti-Slavery Societies also increased. George Brown, founder of the “Globe and Mail” newspaper, and Oliver Mowat, a future premier of the province of Ontario, joined the Toronto Anti-Slavery Society. At the first large and enthusiastic meeting at City Hall, it was resolved that “Slavery is an outrage to the laws of humanity and its continued practice demands the best exertions for its extinction.” The Society further declared that they would raise money to house, feed, and clothe the destitute travelers. Weeks and months spent making their way to freedom took a toll on the bodies and minds of the enslaved. Many died along the way. Still, thirty thousand (a conservative estimate) reached Canada between 1800 and 1860 according to the Anti-Slavery Society. Often upon reaching freedom, former slaves would kneel down, kiss the ground, and thank the good Lord that they were free, and then they would build churches for their spiritual growth and development, as well as that of future generations.

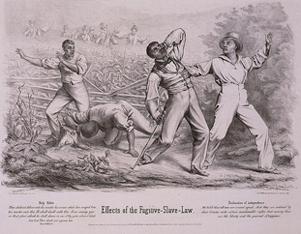

The results of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

Through the encouragement of Southern slave owners, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, dealing a severe blow to the abolitionist movement. This meant that slave owners and their agents had the legal right to pursue and arrest fugitives anywhere in the United States. There were many abuses to this law; bounty-hunters did not discriminate between free Blacks and runaways, and took them both off to slavery in the South. However, the Act stimulated the abolitionist cause, increasing the risks but also the number of freedom seekers fleeing to Canada. One hundred members of a Black Baptist church in Buffalo, New York and almost all of the 114 members of the Baptist Church in Rochester, New York fled to Canada. Black waiters in the Pittsburgh Hotel armed themselves and headed for the Canadian border; they were determined to die rather than be captured.

Land and water travel on the Underground Railroad was made more efficient in the 1850s. All types of boats were used by Underground Railroad agents to reach Canadian shores. The expanding railroads were generally sympathetic to the abolitionist movement. The freedom seekers traveled as regular passengers, or were hidden in freight cars, baggage cars, and even among the livestock.

Integrity and spirituality were prerequisite characteristics for the political, legal, business, and faith leaders who committed their lives and resources to the abolitionist cause.

Underground Railroad: The William Still Story is a co-production of WNED PBS and 90th Parallel Productions Ltd, Toronto.

Underground Railroad: The William Still Story was made by The Canada Media Fund, Canadian National Railway, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting – a private corporation funded by the American People. With additional support from David W. Pretty, Vernon Achber, and Phil Lind. And by PBS.