WBFO

Medina Sandstone's place in history celebrated

From Buckingham Palace and Buffalo's Richardson Olmsted Complex- to the streets of Havana - these are just some of the things made with Medina Sandstone.

By Francis R. Kowsky

Architectural Historian and SUNY Distinguished Professor Emeritus

Henry Hobson Richardson was born in 1838 into an affluent family of Louisiana plantation owners. Like the many of the sons of well-to-do Southerners, Richardson went North to complete his education.

In 1856, he enrolled in Harvard College. After graduating, Richardson determined upon a career in architecture. At the time, no schools of architecture existed in the United States. Rather than become an apprentice, Richardson, who spoke French, decided to go to Paris to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. The curriculum there stressed learning from the architecture of Greece and Rome and the Renaissance. Students were also encouraged to adapt this tradition in new ways to the conditions of modern life. Over the course of the 19th-century, many Americans, including Buffalo’s George Cary, would follow Richardson to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, whose name became synonymous with the Neo-Classical design.

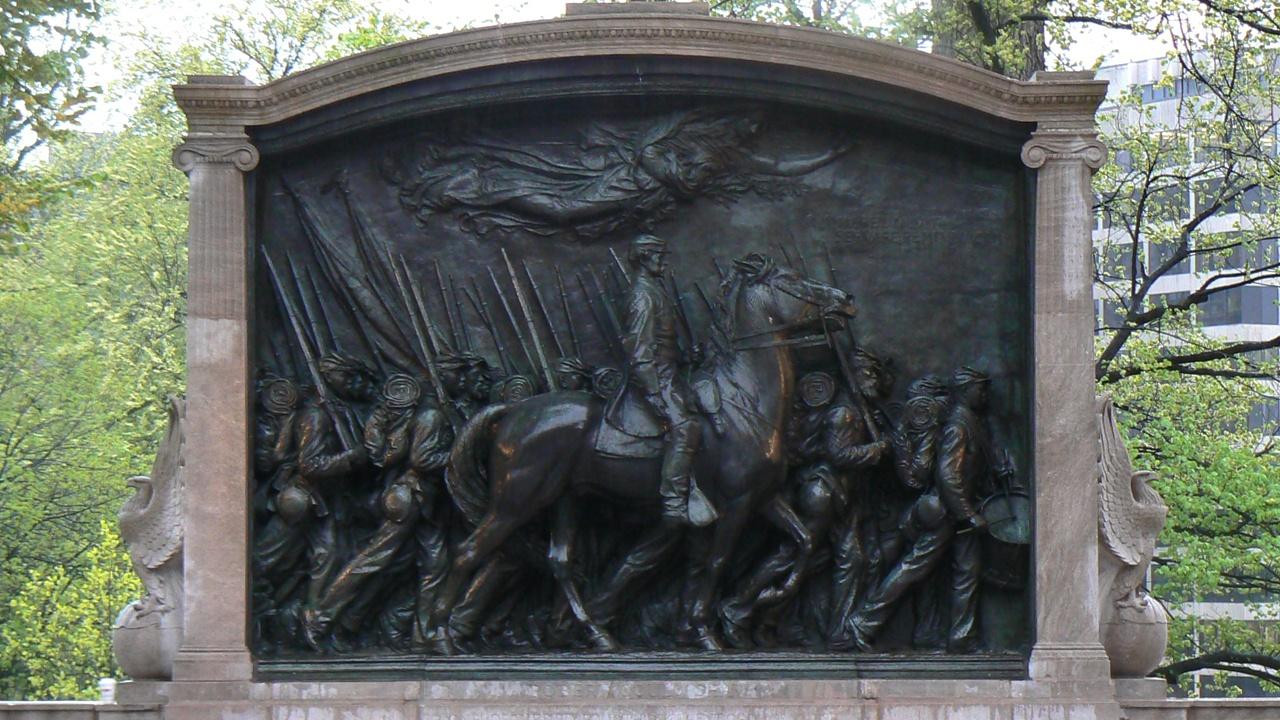

When the Civil War broke out, Richardson was surely torn between loyalty to his old life in the South and to his new life in the North. Moreover, he was engaged to a young woman from a wealthy Boston family. Rather than soldier, he chose to spend the next five years in Paris pursuing his education. After his family lost most of its wealth during the war and could no longer support him, he persevered by finding employment with a French architect. Looking back on this period of Richardson’s life through the window of 1884 when he gladly accepted to design the frame for Augusts Saint-Gaudens’ life-sized bronze relief honoring the service of the African-American 54th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers led by Robert Gould Shaw, one suspects that Richardson had favored the Union cause. (For many years, the Albright-Knox Art Gallery displayed the plaster cast of the Boston memorial in the sculpture court.) In any event, Richardson never returned to his birthplace.

In 1865, Richardson left Paris for New York. The city was the financial and commercial center of the triumphant Union. On the eve of the Gilded Age, it was a good place for a young architect with impeccable Parisian credentials to set up practice. With the help of his father-in-law, Richardson built himself a fine new house on Staten Island where he came to know Frederick Law Olmsted, who owned a farm on the island. Together with Calvert Vaux, a brilliant British architect, Olmsted had designed Central Park in 1858. He and Vaux now occupied the forefront of the nascent profession of landscape architecture. Olmsted and Richardson formed a close friendship that lasted the architect’s entire life.

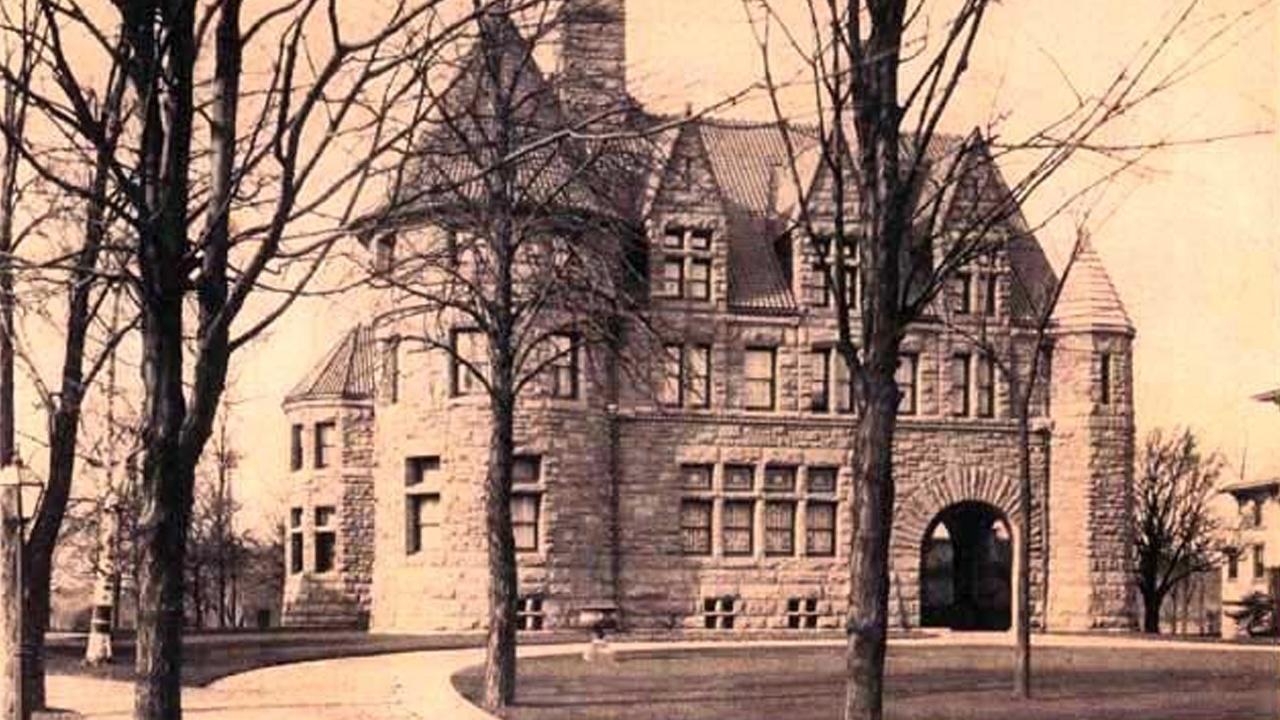

In the summer of 1868, Olmsted answered the invitation of William Dorsheimer, a prominent Buffalo attorney, to come to Buffalo to talk about creating a park for the rising city. Olmsted also must have mentioned Richardson to Dorsheimer, for in October of that year, Dorsheimer commissioned Richardson to design a new house for him at 434 Delaware Avenue. The red brick dwelling, which we can still admire, demonstrated Richardson’s up-to-date knowledge of French domestic architecture. The elegant Second Empire Style house would have looked right at home in a suburb of Paris. The house also became the catalyst for an enduring friendship between Dorsheimer and Richardson.

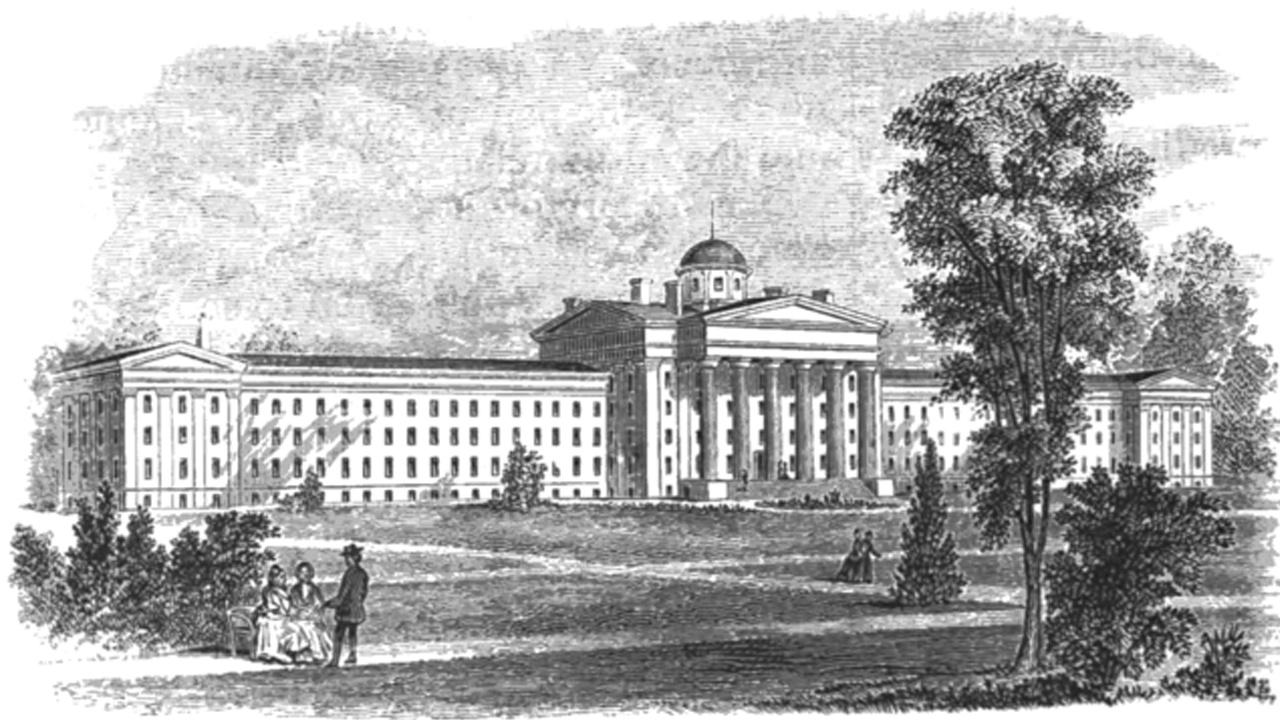

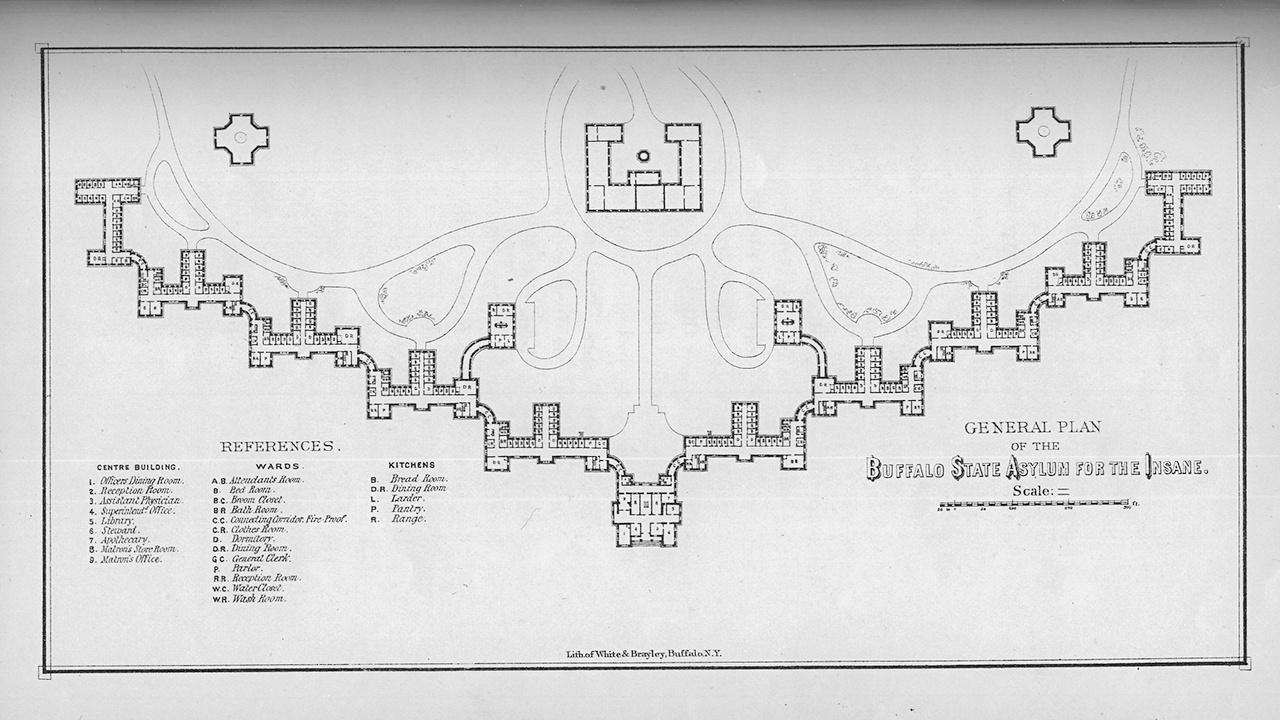

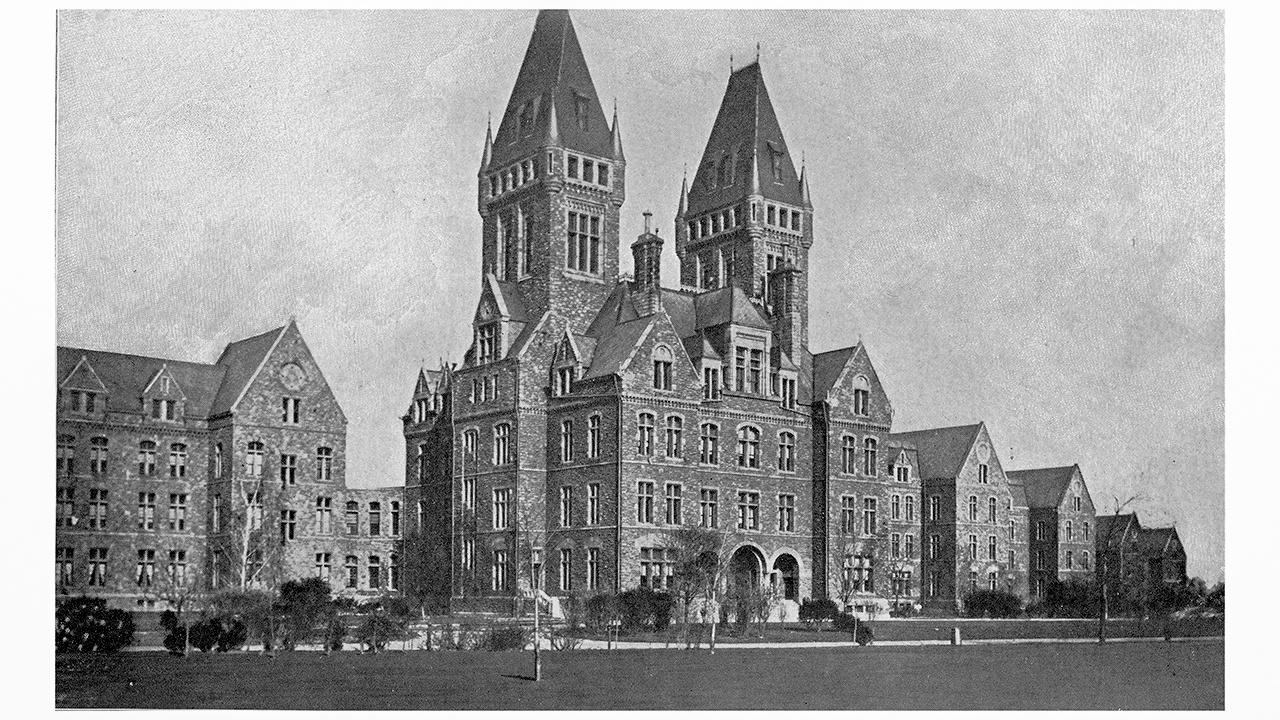

The year after Richardson had designed Dorsheimer’s house, he became involved with the project to erect a large mental hospital in Buffalo. For several decades, New York State had been a leader in providing medical treatment for citizens with mental illness. The Utica Asylum, which opened in 1843, was one of the most renowned mental hospitals in the country. After the war, the need for mental care greatly increased. In 1869, the state designated Buffalo as the site for another large institution. Dr. John P. Gray, director of the Utica Asylum, assumed the role of medical advisor to the project. He based the asylum plan on the example prescribed by the celebrated Quaker physician, Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride. The mammoth structure comprised five patient wards on either side of a central administration building. Young Richardson was chosen to create multi-story buildings from this extended plan. Olmsted and Vaux came to lay out the 200-acre grounds.

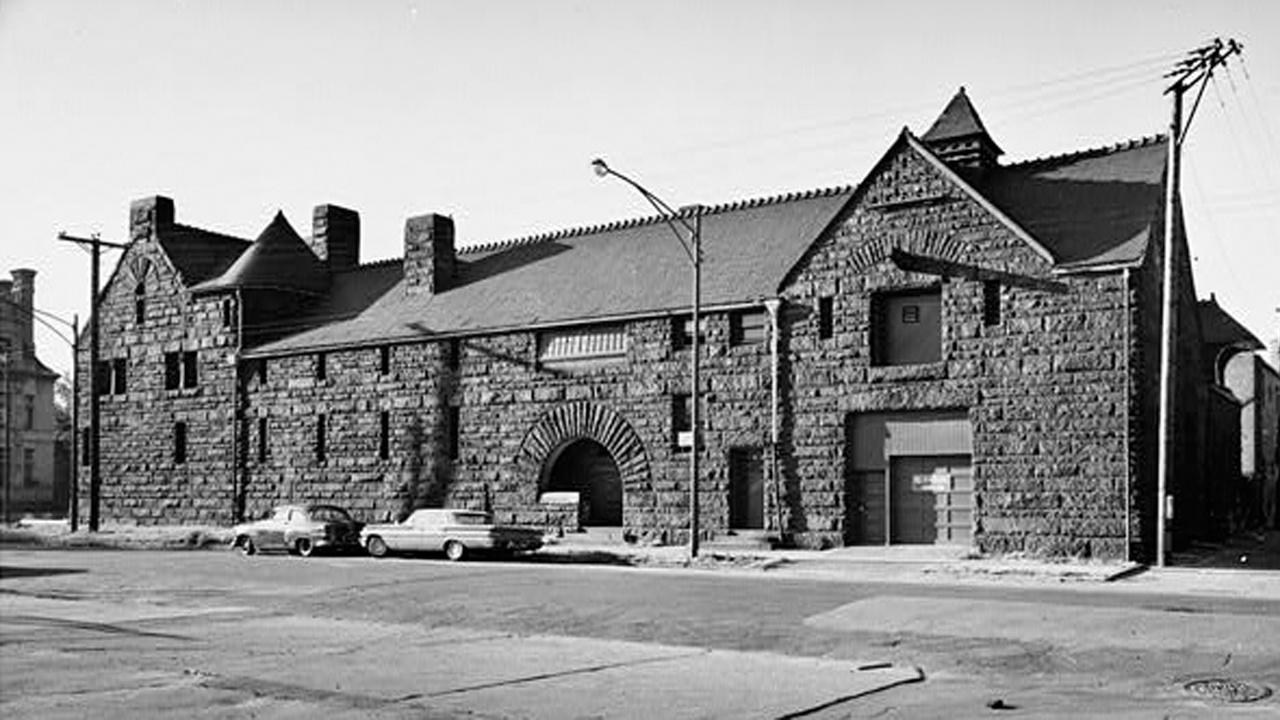

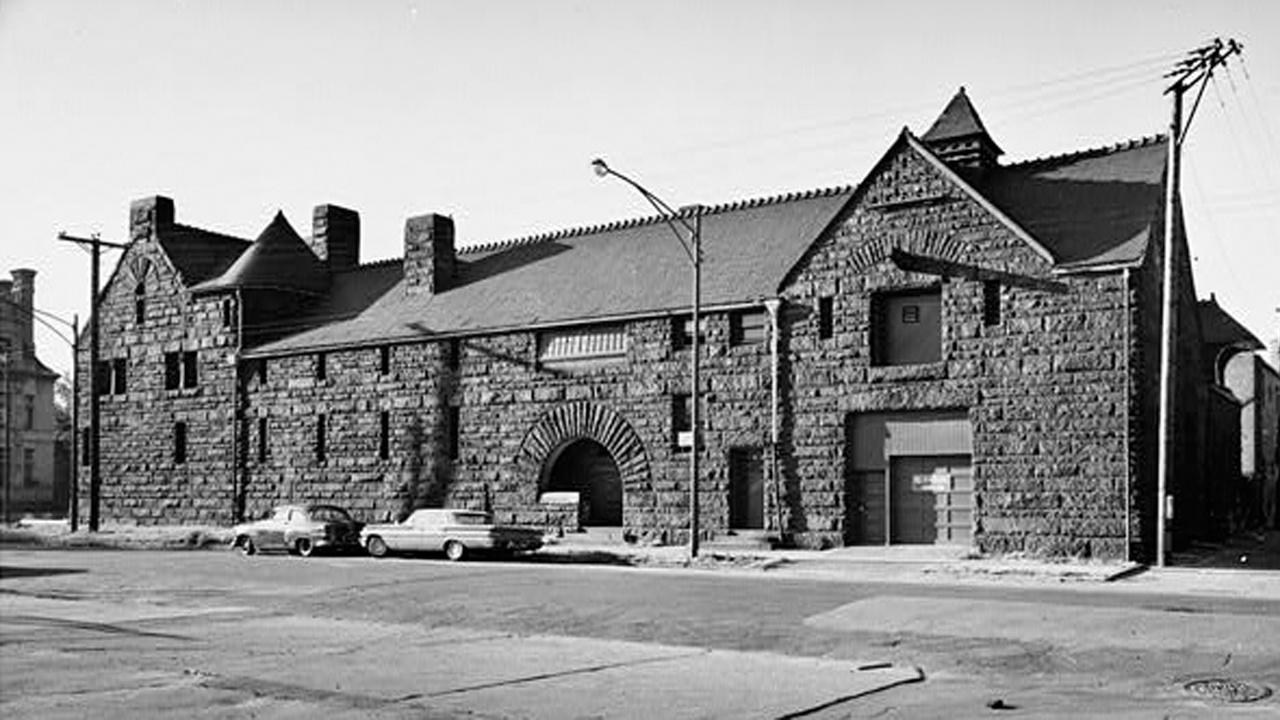

Richardson’s design departed markedly from the elegant Dorsheimer house. Rejecting the Neo-Classical tradition of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he chose instead to look to the architecture of the early middle ages. The round arches, rough stone walls, massive proportions, and many architectural details recall the 12th-century style known as Romanesque, the period that preceded the age of the magnificent Gothic cathedrals. Richardson came to regard the Romanesque style as better suited to express the resolute, straightforward American character than the Second Empire Style, which was identified with the cosmopolitan Paris. By distancing himself from contemporary Europe, he felt he would be free to articulate architecture that would convey the spirit his time and place.

In the years to come, Richardson would perfect this powerful mode of expression which came be known as Richardsonian Romanesque, so personal was his reinterpretation of his sources. With national success under his belt, in 1874, Richardson moved to Brookline, Massachusetts, the wealthiest suburb in America. He was later joined there by Olmsted, whose home and office, Fairsted, bordered his friend’s property. The two men often collaborated on projects.

From Richardson’s drawing board, and with the aid of talented assistants, came plans for some of America’s most famous 19th-century buildings. These include: Boston’s Trinity Church (1872); the New York State Capitol (1875; with Olmsted and Leopold Eidlitz); the Ames Gate Lodge (1881) in North Easton, Massachusetts; the John J. Glessner House (1885) in Chicago; the Mary Fisk Stoughton House (1882) in Cambridge; the Allegheny County Courthouse (1883) in Pittsburgh, and the Marshall Field Store (1885; demolished). Except for the last, all of these have joined the Buffalo State Hospital on the list of National Historic Landmarks.

Buffalo clients were also among those who sought out Richardson. Indeed, if all of his projects for the city had been built and survived, Buffalo would have more buildings by Richardson than any other place. Buffalo may also have inspired his unfulfilled wish to design a grain elevator, for he could have seen many of these hulking wooden structures lining the Buffalo harbor. Richardson’s unbuilt Buffalo projects were a dwelling for Asher P. Nichols (c. 1868), a prominent lawyer; a new house of worship (1871) for Trinity Episcopal Church; a monumental stone arch (1874) to be part of Olmsted’s plan for Niagara Square; and a competition entry for the Young Men’s Association Library (1884; predecessor to the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library).

In February 1886, William Gratwick, who had made a fortune in lumber and lake steamers, commissioned Richardson to design a mansion that would express his life’s achievements. Built of Medina sandstone, the material Richardson had first employed on the Buffalo State Hospital, the dwelling was one of the marvels of Delaware Avenue. Unfortunately, Richardson did not live to see it completed. In late April 1886, at the age of 47, he died of kidney disease. Fond of high living, he had grown from a slender youth to a hearty colossus weighing over 350 pounds. “My god, he looks like his buildings!” exclaimed a German architect when introduced to him. Next to Richardson, his friend Dorsheimer was said to have looked like a pigmy. Richardson’s successors, Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, finished the Gratwick house in 1889. The most short-lived of Richardson’s works, it came down twenty years later.

Although Richardson’s mature career spanned only about seventeen years, his influence on American architecture was profound. The Richardsonian Romanesque endured well beyond Richardson’s all-too-brief lifetime. He was the subject of the first book about an American architect. At Olmsted’s urging, the art critic Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer wrote Henry Hobson Richardson and His Works. It appeared two years after his death. She dedicated her excellent book to Richardson’s loyal assistants whom she said would show by their own works “the greatness of his qualities as an artist and a teacher.” Among that group was Herbert Burdett who came to work in Buffalo.

Locally, prominent buildings bear the stamp of Richardson’s influence. Green & Wicks paid homage to him in the design of the stately First Presbyterian Church (1889) on Symphony circle, and John Coxhead acknowledged the twin-towered administration building at the Buffalo State Hospital in his facade of the Delaware Avenue Baptist Church (1894). John Knox Taylor had his eye on Richardson’s Allegheny County Courthouse when he designed the federal building (1897; present Erie County Community College). Two other buildings here are virtual copies of Richardson works in New England. William Lansing must have had access to Richardson’s plans for the Stoughton house when he built the Coatsworth house (1897) in Lincoln’s Woods Lane. Likewise, the Orchard Park railroad station (1911) mirrors the now-demolished station that Richardson designed for Auburndale, Massachusetts.

“He was successful and influential,” wrote Mariana Van Rensselaer of Richardson, “because his nature was so intensely modern, so thoroughly American.”

Chuck Banas

public domain

public domain

public domain

WBFO

From Buckingham Palace and Buffalo's Richardson Olmsted Complex- to the streets of Havana - these are just some of the things made with Medina Sandstone.

Reimagining a Buffalo Landmark is funded by the Peter C. Cornell Trust, The Zemsky Family and the Members of Buffalo Toronto Public Media.