Hester C. Whitehurst Jeffrey

Born January 1, 1842

Died January 2, 1934

“Hester Jeffrey fascinates me. I think of her as a woman who looked without blinders at the world in which she lived, saw that there needed to be changes made and proactively worked to make those changes. To me, that's her most important legacy.”

— Dr. Susan Goodier, Associate Professor of History, SUNY Oneonta

Hester C. Whitehurst Jeffrey, a tireless activist and leader of women’s clubs in Rochester, NY, was able to overcome incredible racial barriers to push for progress. She became nationally known because of her connection to a famous white suffragist, but her work to uplift Black women in Western New York has rarely been recognized.

Hester Jeffrey was born in 1842 in Norfolk City, VA. Her parents, both free African Americans, sent their children north to live in Boston with an uncle, who ran his home as a stop on the Underground Railroad and welcomed some of the leading minds in abolition to stay there. This set the stage for Jeffrey’s own political activism later in life.

At the age of 23, she married Roswell Jerome Jeffrey. While they lived in Boston, she was very involved in political and social women’s organizations and was active in Black elite society. This public face hid a private tragedy as the Jeffreys attempted to start a family. The couple had four children. None survived childhood.

By 1891, Jerome’s aging stepmother needed the couple’s care, so they relocated to Rochester. At the time of Jeffrey’s arrival, Rochester’s Black population was expanding quickly. She joined the city’s existing associations, including Black women’s social clubs and the suffrage movement, quickly emerging as a respected leader in many activist communities. In Rochester’s club women, Jeffrey found kindred spirits unafraid of hard work, sharing the sentiment: “no work that can emphasize the desire to help others is too difficult to be attempted.”

In 1902, she went a step further andorganized her own group: the Susan B. Anthony Club for Colored Women. The club was philanthropic, supporting the needs of Black mothers and children in Rochester, and advocated for suffrage. In addition to promoting suffrage, club members held classes on topics such as parliamentary law and sought admission for Black women into the University of Rochester.

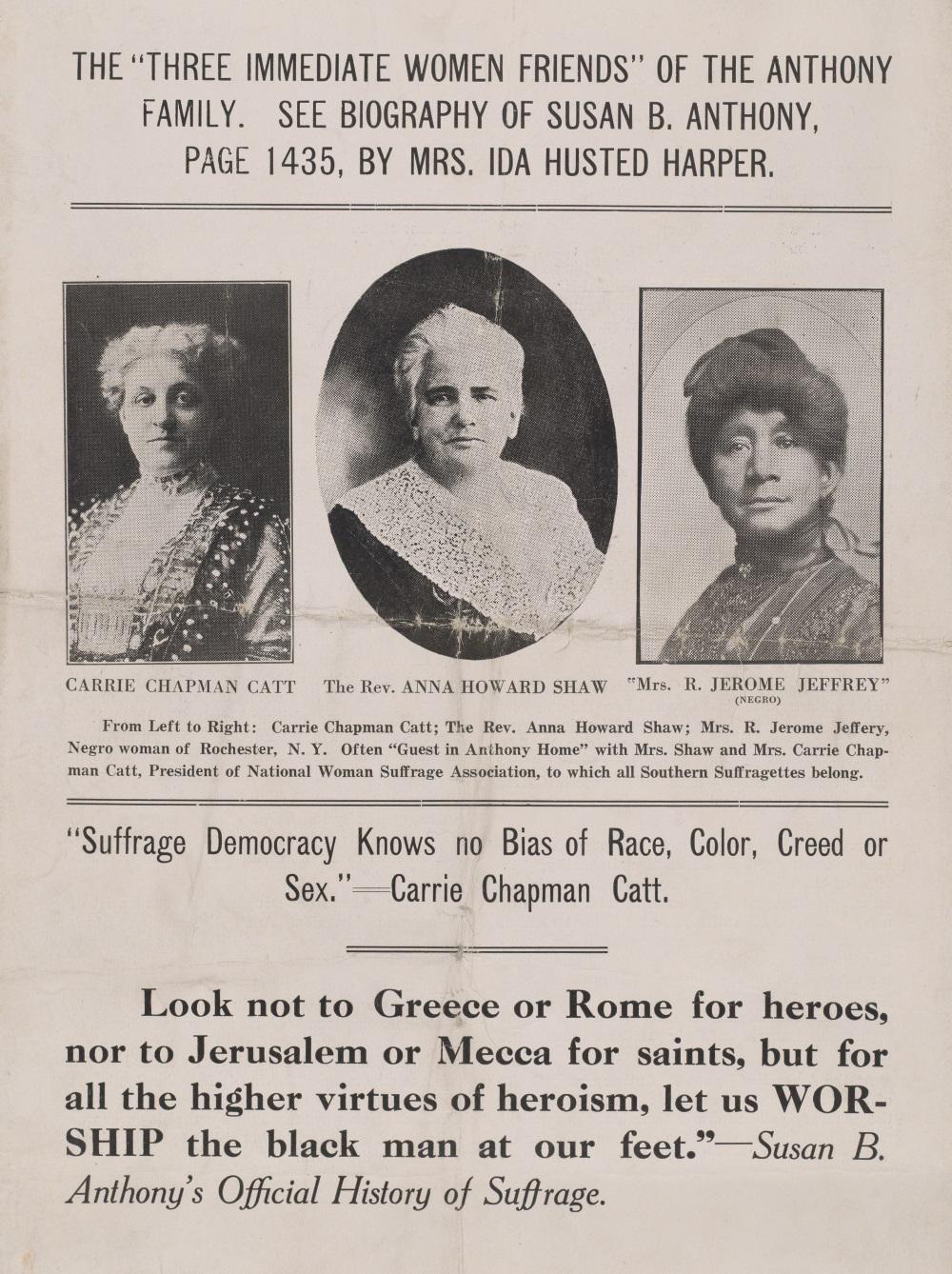

Why name a Black women’s social club after Susan B. Anthony, who often used racist rhetoric in her arguments for suffrage? Anthony was more than the namesake for Jeffrey’s club — she was Jeffrey’s personal friend. The two met when Jeffrey, a member of the Favor Street African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, attended services at the First Unitarian Church. Their shared passion for social justice sparked a friendship.

Church wasn’t the only place where Jeffrey made connections with white activists. She regularly moved between the often-segregated worlds of the National Association of Colored Women and Anthony’s National American Woman Suffrage Association. She reinforced ties between local Black and white suffragists by inviting white Rochester Political Equality Club members to speak at Susan B. Anthony Club for Colored Women meetings.

Jeffrey’s importance, as well as her friendship with Anthony, were recognized when she was selected as the only layperson to eulogize Susan B. Anthony at her funeral in 1906.

”We, the colored people of Rochester, join the world in mourning the loss of our true friend, Susan B. Anthony. Yes, a true friend of our race. Years ago, when it meant a great deal to be a friend to the poor, downtrodden race, Susan B. Anthony stood side by side with ... Frederick Douglass and others, fighting our battles and espousing the cause of an enslaved people.” [We pledge] “to devote our time and energies to the work thou hast left us to do.”

As a tribute to her friend, Jeffrey was instrumental in creating the first memorial for Susan B. Anthony. The memorial, a stained glass window that still hangs at the A.M.E. Zion church, consists of a portrait of Anthony along with her famous statement — “Failure is Impossible.”

Both the eulogy and the memorial illustrate the complicated relationship between African American women and the suffrage movement, with its often racist agenda. Jeffrey’s connection to Anthony is often the only recognition given to her in the history books, but her leadership started long before and lasted long after. She helped found clubs across New York State to promote social change for African Americans and for all women. Jeffrey’s work in so many organizations kept her at the vanguard of Black women’s activism for virtually her entire adult life.

Major support for Discovering New York Suffrage Stories was provided by The National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the Human Endeavor, by the Susan Howarth Foundation, and KeyBank in partnership with First Niagara Foundation. With additional funding from the Fred L. Emerson Foundation and Humanities New York.